By Susan Abernathy Mandy says it’s short for Adventitious Roots, but I think AR stands for Adventitious Researchers. The Oxford English Dictionary defines adventitious as “coming from outside, not native”. This definition fits the current grove of researchers that Dr Rasmussen has transplanted from across the globe into the AR lab. Six of the seven continents have been represented in this AES arboretum over the past seven years at the University of Nottingham and only Antarctica has escaped so far. If you’re reading this and have penguin-esque tendencies, I know of a lab that may be a good fit for you!  Adventitious researchers have emerged from unexpected places like Nigeria, India, Spain, Columbia, Bangladesh, Italy, Germany, Australia, and the US in the way that adventitious roots appear in unusual locations along a stem or leaf. Some of these researchers have barely rooted staying only a short time, while others have stayed several seasons leaving well developed pathways for others to follow. Additionally, Mandy has planted some native UK researchers as well to mix among the transplants that help maintain homeostasis in this everchanging grove in the midlands of England.  Adventitious roots have subgroups that form in different ways and under different stresses. Each adventitious researcher has distinct experiences that they bring to the AR lab that make this grove truly unique. Some researchers support and brace others, growing close to the ground, while others reach out for new holdings high above the rest that stretch the group in new and interesting directions. Still other researchers are more cryptic in their behaviour as they seem to hang in the air not really reaching for anything, all the while absorbing all that they need directly from the air itself.  I am one of a few newly transplanted members of this grove. We have settled into our new environment like re-potted shoots, over the last 6 months. In that time, I have seen some amazing teamwork and unity in the AR lab simultaneously with seasoned researchers migrating to new fields and new transplants just beginning to root. Growing in this unique setting is a very rewarding experience where the diversity adducts with each member. Some of these experiences include different approaches to performing experiments and others involve solving problems. Working together as one lab though, while each member focuses on a different project works to everyone’s benefit because like a colony, information learned on one side of the grove can be sent to members on the other side, preparing them for the best response to external stimuli, environmental stresses, and perceived herbivory!  Sometimes adventitious roots need to be induced to grow where they wouldn’t otherwise emerge. Mandy has harvested staff and post-docs from Australia, Brazil, and Sri Lanka who work additional projects as well as guide new transplants into shooting. These pairings develop into mycorrhizal-like symbiosis where each benefit from the other. On one side there is resource allocation and on the other, the availability of carbon units on which to induce the desired response. In both cases, this results in a healthy equilibrium of exchange and growth within the grove.  As an American living in England, learning the differences between the two countries has proven to be surprising as well as entertaining. Many words are familiar to both countries but have differences in meaning and use. Some are obvious like pound, chips, crisps, tea, post, carriage, bonnet, lifts, and braces. Others were unexpected such as faculty, staff, professor, and college. Some words mean the same in both countries but are pronounced differently like oregano, banana, tomato, potato, pasta, basil, and contribute. Some words mean the same and only the spelling differs such as color, tire, program, and behavior. In addition to words, there are other differences in everyday things that tend to be opposite. Driving is the obvious one with all things left rather than right. However, light switches go down rather than up, doors open out, rather than in, or in rather than out, depending on the location. Rather than opposite, floor numbers in buildings are one number off and one only has to remember to add ‘up’ to understand that 1 floor up is the second floor and ground floor is below ground. Even with the differences between our “common” language and customs, some of my co-workers are having quite another experience. To them, EVERYTHING is different, even the trees! Sue would like to acknowledge the contributions of Khalad Mosharaf to this article. References

5 Comments

Job Application Process!

Given the diversity of cultures and correspondingly, diverse recruiting systems I would like to provide here some guidance on how to apply for an advertised job with our lab. This should also be helpful for applying to other jobs at our university and most probably other UK universities too. Please note there are other official websites listed at the end of this blog for applying to the University of Nottingham so do read those too.

So applying here involves two main steps: 1) the written application and 2) the interview. The written application is an online form with a set of selection criteria. It is extremely important that the responses answer these criteria in detail. I would strongly advise candidates to make an offline document with the selection criteria headings and take time to answer each one. Then copy-paste your thought-through and edited response into the text box of the online form. Make sure you have read the job description and craft your responses with that in mind. When drafting your responses:

Click submit and fingers crossed! So you've been invited for an interview: CONGRATULATIONS!!

For now (and most likely for the foreseeable future) we are inviting people to come in person where feasible and otherwise conducting interviews online - this applies particularly to applicants not within the country to keep our carbon footprint down (however other reasons can be discussed for local applicants as appropriate to maximise accessibility).

The interview itself: we will most likely ask you to present a 5 or 10 minute presentation (check your specific instructions) on something about your experience and why you want this job and we will then follow with 20-30 minute discussion based on a set of questions that we ask every candidate. Remember, specific information relating to your particular interview will be included in the invitation to interview that you receive from HR so do pay close attention to that information. Asking you to give a presentation serves several purposes: 1) we hope it relaxes you a little to talk about something you can practice and should be something you know about (yourself and your ambitions!); 2) it shows us that you can communicate under pressure which is inevitable at some point in almost every job we would be advertising (from conference talks, to industry funders or end-users of the science). So prepare well for this (ideally ask a mentor or colleague to give some feedback on a practice talk!) - have visually interesting slides or props, and make sure you've practiced those first few slides to get past the nerves :) When sending files (like the presentation) please make sure you save the document with YOUR name rather than the title of the talk which will be similar for everyone! The questions in the interview will vary depending on the job but much like for the selection criteria, try to give more than a one-word answer and if you're not sure what we are asking, by all means ask for clarification. Also don't panic if you go off in a different direction to what we're looking for, we'll clarify the question and redirect you - it's normal. We are people too and we ultimately want to hire the person who's the best for the role so we will ask and prompt as needed. There are other websites that talk about body language and things to think about for interviews (see links at the end) but ultimately try to relax and be yourself. I will say a couple of things about online interviews:

Find a room with as little background noise as possible and where there is a strong and steady (as much as possible) internet connection. Try to have a dark background - or at least not a window or light behind you. This is because most webcams (built-in or otherwise) are not good at balancing backlight which means your face will be in complete shadow if there's too much light behind you. It's also best to use headphones directly plugged into your device. When you have found the space and device you will be using check with a friend that the sound and picture are clear using the exact setup (computer, headphones and network connection) you will be using for your interview.

When you log onto the interview link - if there are technical glitches just take a breath.

(you may want to write this as a list and have it next to you during the interview to remind you not to panic and help you try things logically to solve the problem!)

We remember what it's like and understand you will be nervous, it's not something to be worried about in itself! Getting worried about appearing nervous is like a self-perpetuating spiral and there's no need - we know you're nervous, and we'll do our best to prompt and help you settle into the questions.

I hope this helps clarify a bit regarding what we are looking for in job applications! I understand how different the processes can be around the world and I hope this helps everyone understand our processes here! I look forward to reading your applications! Links for further advice

Links for written application advice:

University of Nottingham:

Links for Interview advice:

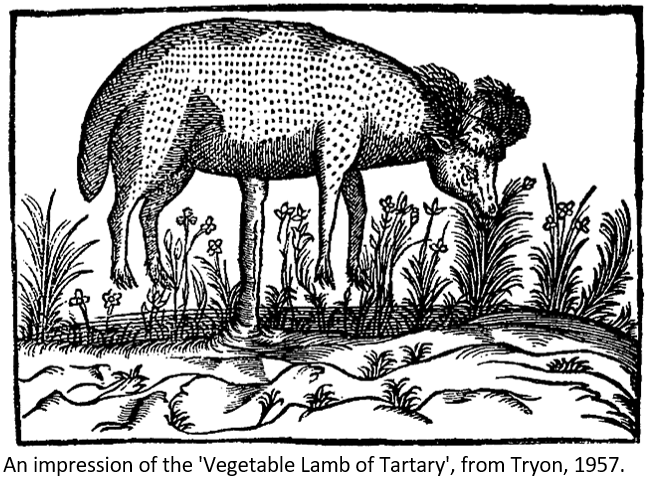

This is a post written by Darwin Hickman on the history of allelopathy. I learnt a lot, and we hope you enjoy! I’ve been a joint PhD student with the University of Nottingham (including the AR_Lab) and Rothamsted Research for four years now, working on interactions between crops and weeds and how we can tip the balance in favour of the crop. Throughout this time, I’ve worn many hats (both literally and figuratively), at turns leaning into the fields of agronomy, weed biology, plant physiology, chemical ecology, soil microbiology and even chemistry (a scary prospect when I started to be sure). Rarely do projects of this nature take such a holistic approach given constraints in time, funding or expertise so I’ve had more opportunity to really delve into this weird and underappreciated area of science. One of the things that I really engaged with, but struggled to find an outlet for, was the way that our understanding of these interactions has developed over time, and how difficult progress has been, and that’s why I’m writing this, because it’s quite the story. I’ve spent a substantial portion of my PhD explaining its core concept: Allelopathy. In honesty, I wasn’t aware of it until I came upon the studentship which I now work on (even as a fledgling weed ecologist), and I think that speaks to its nature as an inherently intangible phenomenon. It says a lot that G. Bruce Williamson in 1990 described the challenge of proving allelopathy as a ‘neck riddle’, the impossibility of which a condemned prisoner would stake his life. A lot of definitions of allelopathy are out there, the first being the succinct summary offered by Hans Molisch in 1937 when he coined the term: “The influence of one plant on another”. More specifically, the most-commonly understood mechanism of allelopathy is that one plant species releases defensive compounds (‘allelochemicals’) to actively inhibit other (usually plant) species which may compete with it, usually from the roots. As such, it’s incredibly difficult to prove, as it is very closely associated with resource competition (which differs in that the antagonistic plant deprives its competitor of something it needs, rather than giving it something it doesn’t want). J. L. Harper, highly quotable visionary in plant ecology, would describe it as “logically impossible to prove that it doesn't happen and perhaps nearly impossible to prove absolutely that it does”. In spite of such difficulty, though, and the slight obscurity of allelopathy, it has a bizarre and fascinating history from long before the days of Harper or Molisch. It started when Theophrastus, ancient Greek philosopher, student of Aristotle, and ‘Father of Botany’, observed in the time of Alexander the Great that chickpea yields declined over successive seasons, the cause of which was unknown at the time. The Roman Pliny the Elder, writing around three centuries later, would note that ‘venoms’, ‘juices’, and ‘heavy shade’ from one plant would affect surrounding plants, in some cases following their removal from soil. To quote the man: “The oak and the olive are parted by such inveterate hatred that if one be planted in the hole from which the other has been dug out, they die, the oak indeed dying if planted near the walnut… on going away they leave their venom behind when the plant is torn up from the root.” Obviously, these suggestions are primitive, but they are strikingly accurate considering the beliefs of the public in this period, that plants were in fact a basic type of animal which slept with their heads in the ground. Such perceptiveness in interpreting natural phenomena is especially salutary when one realises that Pliny’s response to the famously destructive volcanic eruption at Pompeii was to have a bath rather than run for his life. These observations from antiquity, then, gave the impression that something beyond resource competition was occurring between plants, even if it was a largely unknown quantity without a name to describe it. Unfortunately, the Middle Ages would be unkind to allelopathy, perhaps unsurprising for a period whose ideas of natural history involved the manticore and the cockatrice (although in fairness, Pliny had written about his fair share of bizarre mythological beasties). One accepted myth from this time was that of the ‘Vegetable Lamb of Tartary’, a bizarre beast which resembled a sheep attached to a plant stem. The idea was that this poor creature would ravenously eat all plants around it, then starve to death and wilt away when it could not find further food, conveniently to the point that all that was left to indicate its presence was a ring of desolation. In actual fact, this story was inspired by observations of wool-like tree cotton, and the bizarre and ovine form of the woolly barometz fern rhizome, as well as some misidentified allelopathic effects. Allelopathy would remain at least partially in the dark following the Scientific Revolution in the West. Erasmus Darwin in his Loves of Plants, a collection of poems and scientific notes concerning botany, makes great reference to the Upas tree of Java, the ‘Hydra-tree of Death’, as he calls it. This tree was supposedly not just allelopathic to other plants but toxic to all life for around 20 miles, at least according to the testimony of a Dutch surgeon named Foersch: “The Bohun-Upas… is surrounded on all sides by a circle of high hills and mountains; and the country round it… is entirely barren. Not a tree, nor a shrub, nor even the least plant or grass is to be seen.” In a peculiar (if highly unethical) slice of early Science, Darwin Sr. Sr. would detail in his notes on the Upas that he obtained some seeds (the source of which was not explained), fed them to a dog, and observed that it convulsed and died. What Foersch did not mention, however, was that the Upas he saw was close to the smoking vent of a volcano (who knew volcanoes had so much to do with this subject?), the toxic gases of which were the true cause of the reported devastation. The source of Erasmus’ killer seeds is lost to history. In the modern day, an Upas tree sits in the middle of the fourth largest city in Malaysia, home to over half a million people, which is named after the species: Ipoh. Incidentally, my grandfather was based in Ipoh for military service in the 1950s and showed no signs of being poisoned by an accursed tree. Elsewhere, however, the beginnings of modern allelopathy were taking shape. As early as 1727, ‘Dutch Hippocrates’ Herman Boerhaave was suggesting that chemical compounds were emitted from plant roots. This hypothesis was mostly proven by fellow Dutchman and part-time military physician Sebald Brugmans with the collection of droplets (admittedly of unknown composition) from root tips of darnel ryegrass. These piecemeal advancements set the table for Augustin de Candolle, colleague of Lamarck and inspiration for Charles Darwin, in the early 1800s. He, and a student by the name of Macaire-Princep, grew plants in various solutions which reacted with exudate compounds to confirm their presence. From this, de Candolle rationalised and advocated the use of crop rotation as an agronomic approach to avoid ‘soil sickness’, the mysterious decline of crop yield with repeated sowings. So, thanks to de Candolle and his predecessors, it was apparent that something was happening, but the next step required was the identification of some offending compounds. Juglone, or to use its full name, 5-hydroxy-1,4-naphthalenedione, would be isolated from black walnut in the latter half of the 19th Century, explaining the ‘heavy shade’ that Pliny had alluded to, as well as toxicity of these plant parts to other species both inside and outside of the plant kingdom. By the early 1900s, the USDA Bureau of Soils, specifically Oswald Schreiner and Edmund Shorey, would isolate multiple chemical compounds from agricultural soils, such as arginine and histidine, known to be of plant origin. Across the Atlantic, gentleman scientist Percival Spencer de Umfreville Pickering (Spencer to his friends), and the 11th Duke of Bedford, were venturing into pioneering physiological work in their fruit orchards in Woburn. Part of this pursuit may have been the former’s attempts to remain engaged in plant chemistry in spite of ill health, having lost his eye in a lab explosion in 1890. Pickering would bring these experiments into his own glasshouses, noting that washings from soil where mustard plants had grown were inhibitory to a variety of fruit plants in 1917. He used this as evidence that allelopathy (although still unnamed at this point) was a widespread phenomenon. Of course, this needed a name, which was where Molisch came in in 1937.  Pickering’s allelopathy experiment from 1917: The large pots contain fruit tree saplings, the small pots in front contain mustard plants. On the left, mustard root exudates are freely washed into the larger pot, severely inhibiting the growth of the fruit sapling. In the middle, these exudates cannot enter the growth medium of the sapling, which has developed much more. On the right, the negative control with no mustard and a large, healthy sapling. (Pickering, 1917). At this point then, allelopathy was indisputably ‘a thing’, but attempts to observe and explore it in the field would be scant until the 1950s. Enter, Cornelius Muller. His domain was the deserts of Colorado and Southern California, theoretically a simplified ecosystem from which to untangle these many interlinked interactions between shrubs. Even here, he would state (correctly) in 1953 that “The natural habitat… is far too intricate a system of influences and factors, physical and biological, to hope that there may be found a single factor controlling the complicated life of a perennial species”. In spite of this defeatist tone, Muller would eventually detail with comprehension the allelopathy of purple sage 13 years later, describing both in-field radial inhibition of grasses and similar effects against cucumber in the lab. Another 12 years thereafter, he and a co-worker, Stephen Gliessman, would determine the allelopathic dominance of bracken with a similar degree of diligence. Meanwhile, Elroy Rice and his colleagues delved into allelopathy in agriculture in the 1960s to the 1980s, noting broad-scale allelopathy in Johnsongrass, sunflower, broomsedge, and a variety of other plant species. With this background, Rice produced a book, simply titled ‘Allelopathy’ in 1975 which summarised work to that date, and remains influential in the field, essentially setting the stage for modern allelopathy studies. Strides forward have been made by some in the following years. Broad-scale allelopathy has been reported by rice, leading to the promotion of breeding programmes to optimise weed suppression. Sorghum allelopathy has been tracked from field to molecule- specifically the potent benzoquinone allelochemical sorgoleone. Phenolic acids have been extensively studied and their various bioactivities hotly debated. But there is still a great deal of progress to be made. As noted, Williamson in the 1990s basically claimed the definitive isolation of allelopathy to be impossible. He, like numerous influential workers, set frameworks for a best possible verification of allelopathy occurring, so difficult that modern works rarely satisfy them entirely. John T. Romeo in 2000 noted of allelopathy works that “Greater than 40% of the papers submitted… are rejected… a disproportionately higher percentage than in other subdisciplines of chemical ecology”, due in large part to this difficulty. In particular he singled out the ‘grind and find’ approach, producing whole-plant extracts with little ecological relevance but great bioactive potential, and the ‘thrill of the kill’ approach which prioritises the elucidation of a toxic effect regardless of dose or its practicality. No doubt considering Muller and Rice, Romeo argued that “the pressures of survival in science today focus overwhelmingly on frequent publication and, therefore, usually preclude the kinds of exhaustive work necessary to make a convincing case for allelopathy, at least the components of the process need to be done with precision and rigour”. A number of reviews have been presented in the following years which philosophise on allelopathy and how to most effectively investigate the subject, but there are still issues with respectability. Cruelly, a 2003 piece in Science entitled ‘Making Allelopathy Respectable’ was marred when the work it spotlighted was affected by a series of retractions and alterations resulting from a lack of reproducibility. Even today, then, it remains the case that, as Romeo says, “Within chemical ecology, allelopathy remains the poor stepchild, often lacking in legitimacy and respectability”. With the looming twin spectres of widespread resistance to novel herbicides and increasingly stringent regulation of these formulations, the poor reputation of allelopathy needs to change for the benefit of modern ecology. Through integrity and diligence, I believe it will. Further reading and sources:

This is my first blog in AGES! How to begin....I think I can't avoid a few words about the pandemic.... I know the pandemic has been hard in different ways for lots of people. Work-wise I've always depended heavily on technology with half my lab based in different institutions and I was already using hybrid teaching before the pandemic so in some ways I was able to adjust perhaps a little smoother than others. On a personal level though I've found the isolation from family and friends extremely challenging. Those of you who don't know me, I'm Australian with all my family and a large network of life-long friends all still in Australia, while I live and work in the UK. I normally try to make it home to Australia for Christmas every two years. My immediate family live in a rural area - the black summer fires of 2019 began in my home region - making video calls patchy at best so we use skype or Whatsapp as a phone rather than for video calls. So between trips home I don't see my family at all. Christmas of 2020 would have been the 'due' trip home but with borders closed from March 2020 and only just reopening a few weeks ago I've not seen family since Christmas 2018 - that's before the fires. Now the first thing I want to say is I'm glad the borders were closed - my family were basically business as usual for that time. The flip side of the isolation that puts them at risk of bushfires, also protects them somewhat from the comparatively small COVID outbreaks that escaped the capitals during the pre-vaccine part of the pandemic. With all my family 'at-risk' with additional health challenges I am incredibly grateful that they have made it through and I'm not immediately jumping on the 2 flights and 10 hr train trip to see them at the risk of bringing the virus with me. But it has been very isolating with comparatively few people around me in a similar exile from their family. Particularly hard has been hearing others complain about not being able to go to Portugal for their summer break or not see their family for a month during our UK lockdowns when they see family every other week. I understand that's hard too in the circumstances and that those people mean no harm, but hearing that kind of thing has made my own isolation that much harder. I share this now (and maybe should have earlier) because if you are a foreigner in your chosen country - you are not alone. Like everyone, I've tried to make the best of the situation and focused on supporting others when I could - particularly the Christmas of 2020 when many of our international students were also stuck in the UK. I hosted a virtual "Christmas Fam" over the break with video calls a couple times a week, and for much of the online year, shared weird facts or pictures with enviro students and ran occasional virtual pub quizzes. Anything to take all our minds off the otherwise bleak situation. And I have to say the students have been an inspiration - my third years reaching out across the globe to interview scientists for their documentary videos, project students collecting data from local parks and greenspaces and tutees laughing about how they now know there's such thing as a Saturday morning (having gone to bed at a reasonable hour on a Friday night)! While the past year has seen a big increase in workloads with in person and online switching on and off depending on the circumstances, there has also been some big progress. The lab has grown with Sandra who joined us in September from Columbia on an Envision PhD studentship and Alex who joined us mid October as a 6-month technician on a Tree Production Innovation Fund grant and we are finalising two other PhD studentships as we speak! Also the first of 3 PhD submissions has happened with Darwin submitted at the end of Feb. More formal celebrations to come! We have also secured several grants in the past 6 months. The first is a Royal Society International Exchange grant with Erin Sparks (University of Delaware) to establish our work on support-supply trade-offs in Maize. The next was a Tree Production Innovation Fund 6-month pilot study to screen rooting ability of UK broadleaf tree species and most recently we have just discovered we were successful in securing a 3 year KTP grant in partnership with Whetman Plants International. More on all of these in due course!

So it's been a challenging few years, but change is coming. I do hope things don't go back to 'normal' - there have been major advancements as a result of the pandemic. For example streaming lessons live (I use a laptop pointed at the front of the room with a Teams meeting and an earpod in one ear) has meant students not able to make it in person for any reason can still interact - and I've not heard a single sniffle of cough since I started teaching this way! (No more freshers flu for me!). Similarly the flexibility works really well for me (actually flexibility should work for everyone because they have the choice not to work at home too!), saving me time, improving productivity, using less fuel to commute and has improving my overall health (time I don't spend commuting I spend getting exercise). But I am very much looking forward to travel resuming - for family and for science! Nothing beats a good pub meal for sharing new ideas! So I shall end my update blog here, but there will be more soon. As we begin to prepare for the possibility of beginning the new academic year online, a key point being discussed is how to create a sense of connectedness in isolation. As nicely summed up in a webinar from AdvanceHE last week (see here for members) connectedness is about interaction with the campus (including available services), with peers (both socially and academically) and with the lecturers. This discussion triggered me to reflect on my own undergraduate experience. I took an atypical path as an undergraduate starting an undergraduate degree in an engineering specialism before quitting and changing to horticulture as an external student and finally transferring to internal study from second year at The University of Queensland where I completed my bachelor of science (ecology/botany). These different experiences all had different features and provide a useful opportunity to compare external (with strong similarities to online learning) with internal pros and cons. (at the end of this blog is a list of useful links with different online teaching ideas). So I'm going to take you on a journey. Close your eyes (ok maybe leave them open enough to read!). Imagine you are 18, having grown up on a farm 60 km from the nearest town where you attended high school (a journey which took 90 minutes each way on the only school bus). For the last 6 years you studied really hard, attended every science or engineering summer school that your parents could get you to (which required begging financial support from organisers as we had no money) and you scraped through with a mark high enough to secure a local scholarship which covers textbooks and a computer). This is ,the beginning of my undergraduate (and adult) journey. Filled with excitement I moved 500 km away to Sydney into a share-house (we couldn't afford college/hall accommodation) with 4 others. The excitement continues into the first week of classes as they tell us about the fascinating subjects we are going to learn. However as semester gets underway the excitement gives way to stress as the material gets harder -fast. I fail a maths test. First test ever in my life I failed. I try to access my tutor (demonstrators in UK terms). No-one is available to help. I am just one of thousands of first year engineering students. They are all doing so well. I'm not good enough. I'm no-one. Parallel to this, I had never lived away from my parents for any length of time before this, and now they were 500 km away. I was homesick. In the end I quit. The day that fees kick in for the year (about half way through semester) I pulled out and called my parents in tears, afraid of their disappointment. They had spent so much time and energy helping get me the best possible opportunities despite our rural location. Dad drove the 500 km the next day to bring me home. I cried all the way back - but this time because I realised Dad wasn't disappointed in me. He wanted me to be happy. That's why they had done all they had. Not so I would do engineering but so I would be happy. This was a key learning point for me personally. I believe some of the most important things first years learn, are about themselves. Let’s pause on this journey and think about connectedness for a minute. The first lesson here I think is that part of first year is actually learning about disconnecting (not completely of course) from the protection of living at home. For our international students this is even more extreme with them also learning to disconnect a little from their own culture and adapt to a new one. How do we enable them to learn about themselves in these ways via online learning?? In the UK (at least in my sphere of experience) the first year marks are focused on progression to second year - which I think is good because it allows space for students to learn about academic expectations, learn about themselves, adjust to living away from home and make a few mistakes along the way. But unless we are careful, this space wont exist for students starting their first year online. Instead they will have to adjust to living away from home later in their degree when the marks count more. The second point on connectedness is that, although I was connected to the campus, I did not feel connected to my peers. Even though there were only 15 in my specialism, we had classes with all the thousands of other engineering first years and I felt isolated despite the masses. And in the end this is what triggered my quitting …I'll leave this point here and come back to it later. Fast forward 6 months. I've settled back in at home and enrolled in bachelor of horticulture as an external student. Our external cohort is something like 30 students and we do all the same material that the internal students do, except we don't go to lectures (back then internal students actually attended most of their lectures!). We are sent lecture notes, example questions and tutorial activities which we receive feedback on from the lecturer via email, and my timetable was mine to decide and I could work at a pace that suited me. ----I need to pause here and explain this was 20 years ago (yes now I feel old!) and our online environment was Blackboard and email. There was no real-time discussion (I didn't even have a mobile phone yet!). So communication was almost exclusively email--- We did our practicals during residential visits to the campus where we stayed in college/hall accommodation and did 2 pracs per day for 4 days straight for each module during the uni breaks at Easter and in October. In terms of connectivity: Despite the distance, I felt connected to my peers - we were given each other's emails at beginning of semester and we interacted a little (in some classes) on Blackboard. Additionally as many of us did the same modules, we spent almost 2 weeks together during residentials. This meant we got to know each other very well and made subsequent communications much easier. This is fairly similar to the change in relationships I see coming out of field trips. If this is to be replicated online I think smaller groups (for example our personal tutor groups) having regular activities (not all academic) using video calling will be important. Of course during this time I didn't learn about reducing the connectivity with 'home' as I still spent a lot of my time with my parents or at my friends' houses in the nearby town. But I did learn in 'my space' at my pace. The biggest negative to being external was in terms of learning during residentials. We crammed so many practicals into 4 days - some of which we hadn't even covered the theory for yet - which means I honestly cannot remember any of the practicals or the learning that should have occurred. I fear this is also likely to be the outcome of short-fat modules that cram a whole semester into just a few weeks. I also found (20 years ago) that getting help with the harder material in second year had challenges as an external student. I couldn't knock on my lecturers door and ask them to explain something. They did their best but conversations with questions and answers could take a week or more to solve. At this point I had been living on the gold coast with a boyfriend (had learnt to disconnect (a tiny bit) from my family home) and so I thought I would go internal at the University of Queensland which also meant re-starting second year. This experience was amazing. 8 am on the first Monday morning was Plant Science. The same 24 students I went to almost every class with from that hour onwards. I made life-long friends in that class and the lecturers are now some of my research collaborators. The whole degree was very research based with a lot of group work, semester-long experiments and field work. All of which meant I felt connected with both my peers and my lecturers. And the culture around me was of life on campus - we did almost everything on campus (except sleep, and I waitressed 3-4 nights a week to help pay my rent) - in fact the culture was influenced by the campus (even campus botany!) in that when the jacarandas flowered it meant exams were almost upon us! This is where my undergraduate journey transitions to honours and onto government/industry research.  When I click my fingers, you will wake, completely yourself (yes I'm assuming you are either hypnotised or asleep by now!). Returning to the current situation we have many tools that can enable us to make the most of both worlds - but what is it we can take from this experience of external and internal study modes:

Collaborative software like Microsoft Teams allows a space for many of these things to occur but the challenge now is how we design activities that support connectivity with peers, staff and somehow with campus (which to begin might be a virtual campus). I've written previously about my third year class and using Microsoft Teams for group assignments (here) and about using mobile apps for helping connect lectures to practicals (which could also be done as a virtual or local treasure hunt). The treasure hunt could potentially be used to help connect students to campus by getting them to find webpages with the appropriate support services, or even using google earth to see how it actually looks. These are not the solutions to everything, or the only solutions out there (see links below for other locations to get ideas) but I hope this blog helps to identify pitfalls and benefits of past internal and external experiences. Since it is clearly possible to feel isolated while surrounded by 1000 students (as I was in engineering) I honestly believe that together we can make all learning environments better (and more resilient) for the future. Links: https://www.arlab.co.uk/teaching-with-microsoft-teams.html https://www.advance-he.ac.uk/ https://en.actionbound.com/ https://digitaleducationpractices.com/2020/04/28/episode-1-transitioning-from-in-person-to-virtual-workshops-without-much-notice/ https://blog.ucem.ac.uk/onlineeducation/ Additional links: Below are a few articles from 'Tomorrows Professor':

With the switch to online learning being forced on many rather rapidly, I've received a lot of questions about my experience, having used Microsoft Teams since the beginning of semester. With that in mind, I've uploaded tutorial notes here and will continue to add short instruction videos on that page as I make them to help others learn as quickly and painlessly as possible. First I'll list some key ideas that I've had more time to think about throughout semester. I'll then explain my module and why I chose to use Microsoft Teams right from the beginning of semester. After a reflection of how things have gone so far, I'll explain the key changes that I'll be implementing as a result of enforced online teaching (and I've included some nice plant pictures to help everyone feel better!). To begin I want to make a few key points that I've had more time to think about since the beginning of semester:

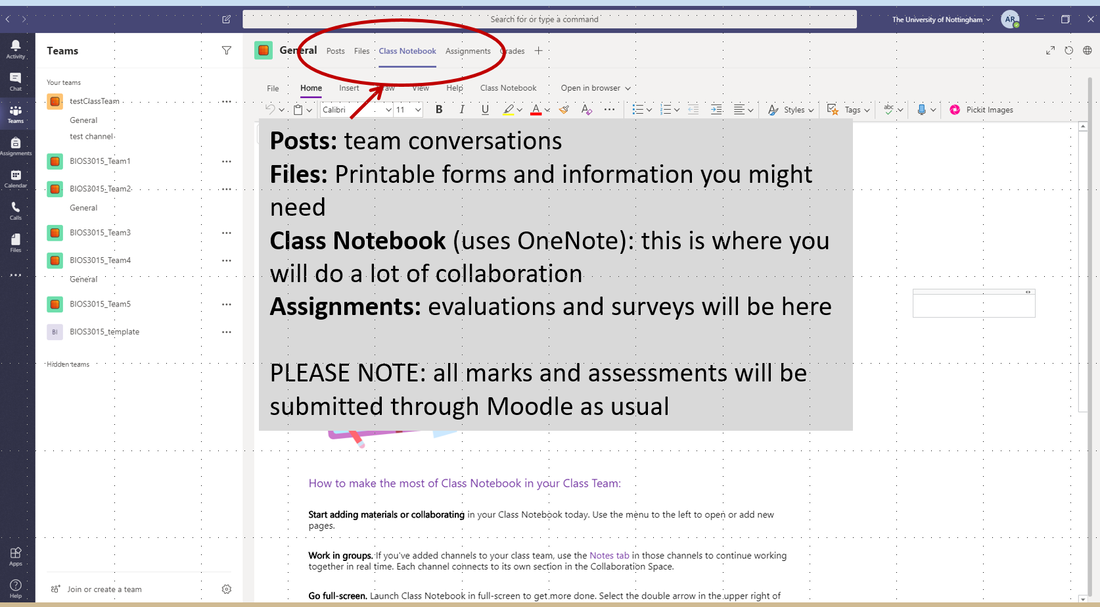

My experience so far: I've been using Microsoft Teams all semester and I thought it worth giving a progress report here as everyone transitions. I've provided some context for the module and how we've been using Teams. I'm also providing tutorial notes HERE and will upload short instruction videos as I make them. My module: 3rd year class Plants and the Soil Environment at the University of Nottingham, UK. Module content: plant adaptations to different soil environments (drought, flood, salinity, heavy metals, nutrient deficiency, and includes plant-plant interactions (both allelopathy and via soil biotic interactions), and biofortification. Contact time: 3 hours once a week. Teaching strategies: traditional lectures for each of the themes, workshops centred around their assessment and a computer lab on root image analysis techniques. Assessment: Poster and storyboard (week 5; 20%), 10-15 minute documentary about one of the themes mentioned above (due second last teaching week; 70%) and 4 compulsory workshops (total 10%). I chose to start using Microsoft Teams this year right from the beginning because:

The assessment- as it happens! Part 1 (happened in week 5): poster and storyboard (20%). The poster needed to have science (less focus on graphical mastery!) and they needed to be able to talk me through the science. The storyboard was a scene-by-scene outline of what their documentary video will contain (ie demonstration that they've thought about the logical flow of ideas). I gave them feedback the same day on the storyboard and later that week for the posters (the delay was only because of the strike action - I would otherwise have provided the poster feedback the same day too). Part 2: 10-15 minute Documentary video (70%) - about one theme related to the module. This is currently still underway. The students have been encouraged to film (using mobile phones or normal cameras) footage or diagram explanations or interviews with other academics from the region (both at Nottingham and surrounding institutions). For this I've been in touch with our Media Team and the Ethics Committee to ensure students are aware of wider GDPR, copyright and safety issues associated with the task. The advantage of teams was that I could set up a class notebook (which uses OneNote embedded automatically in Teams) with sections for each set of information they might need - this means they are not bombarded with lots of files all at once in one place. It's all available all the time, but in partitioned locations that are relevant at different times during the process. Students could then adapt their team notebook as they choose. Copies of all information documents are also uploaded to the Files folder in each of their teams (and also on Moodle for good measure). As students are using different devices and different operating systems I've provided links (in their team notebooks) to OpenSource programs that run on most devices and links to forums where the options have been discussed so they can make their own decisions. This is all more in-line with real world scenarios than our typical strategies of providing students with every program we think they should use and empowers them to make decisions (I also find they are more tech savvy than me and already using video related programs and between their teams of 4 they seem to be doing well solving most challenges so far). Part 3: compulsory team training sessions. There are 4 compulsory classes throughout semester. We have two already. The next will happen right before Easter (and will now be online only) and the other is the week the assignment is due. These are based on my previously published team training package (see here - link). In total these are worth 10%. The fourth team training session gets the students to discuss what the authorship order would be if this were to be a scientific publication (and I allow 4 equal first authors if they decide that's appropriate!). They will then be asked to submit a form with their respective contributions as part of their final submission and if a team has had unequal efforts I will scale the 70% video mark accordingly. This has been discussed with all students at both compulsory sessions so far, is in the module handout (on Moodle and on Teams) and will be reminded in each of the upcoming compulsory sessions. Scaling will only happen if challenges are raised with me prior to submission. - all of this is yet to come so watch this space! Reflection so far: I was very impressed with the depth of understanding demonstrated in the posters - far deeper than any individual lecture that I had given (this was my hope as we have limited time in class). They have all been encouraged to watch each other's poster explanation (this would normally have been done in a compulsory session except the strike action meant I had them video their explanation during that normal class time and upload it to a Team with the whole class). They will also be part of the final marking so they are getting 3 different forms of explanation for the same key ideas in addition to their own repeated viewing of their team's topic during the editing process. Getting started with Microsoft Teams was challenging and I had the help of our Technologies support person. But once we got it started and I worked out where everything was I've been finding it works brilliantly for teaching like this. I've also found the students have adapted really well even though the week I was planning to train them, Microsoft Teams was experiencing technical difficulties! I gave them screen shots in the tutorial document uploaded already to my webpage and now they are coordinating their efforts almost exclusively through teams. An interesting side note - I set up a Team for the whole class when we were having major traffic issues and floods which coincided with a compulsory session with the intention that students unable to attend in person could still interact during the session. They also used this team to upload their posters and provide each other with constructive feedback. Since then I've been posting all class-wide updates to that Team - no-one ever replies to that page - but they are all having lots of discussions and asking me questions from within their smaller assignment teams of 4 - including about information provided on the full class page. This really highlights the benefit of having smaller teams during online discussions - more personal and less scary to raise issues in a group they feel they know a bit better. COVID-19

All of the above has already been going on all semester. We are now being told to teach remotely and fortuitously this class and these students are well prepared for the uncertainty to come. Changes that I've made since the decision for online teaching:

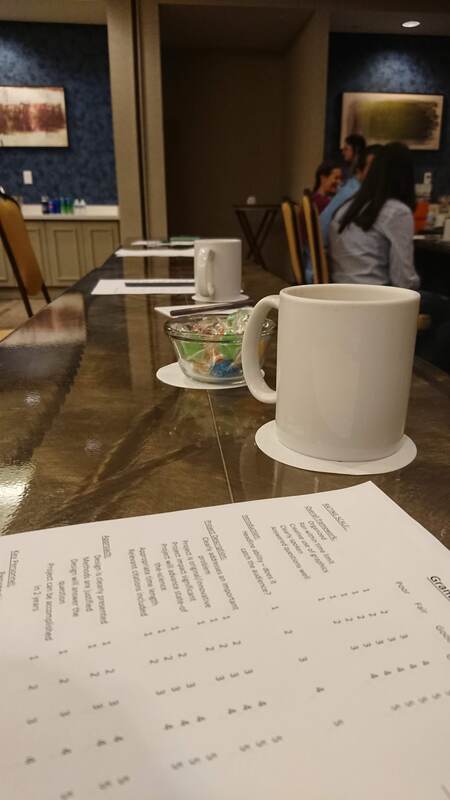

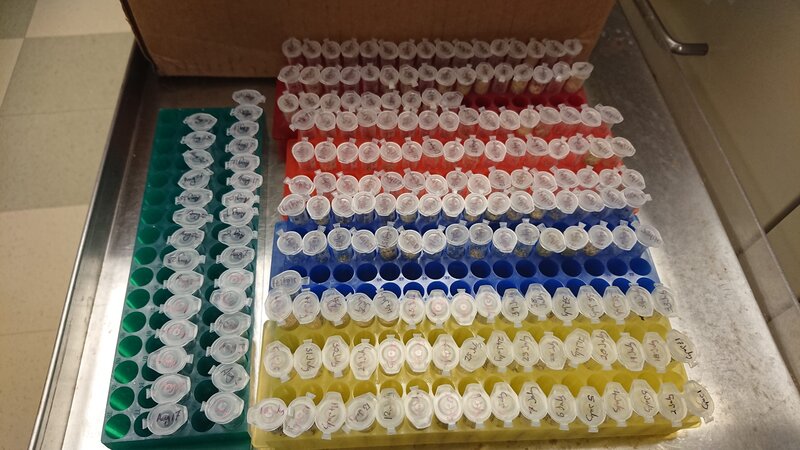

With the turning of the leaves, it is with sadness that this is the third and final travel blog for this summer. It has been a busy, productive and fun 2 months abroad. My last blog was the final day of the ASPB Plant Biology meeting in San Jose before flying back to Delaware. I had just one day in Newark before flying again, this time with Erin to the root workshop held in Orlando and organised by the University of Florida. This was a rare experience of been surrounded by people who also understand the importance of whole plant physiology! The workshop was focused on root physiology and included talks, a field visit, student projects and debates. As invited speakers, Erin and I stayed the week and had the pleasure to not only see all the talks and learn about the latest techniques (aside from our own) but to get to know the students and other organisers better. We found there are lots of synergies between our research interests and I look forward to some great new collaborations. Since Erin and I were staying at Disney Springs, we decided a visit to the Epcot centre at Disney World was necessary. We had a fun day exploring the park and networking of course! We particularly enjoyed 'The Land' ride which took us through a range of different soil-based, hydroponics, aeroponics and aquaponics systems of growing food. We even found some great brace roots on their maize plot. Returning to Delaware we had a grant due and our two glasshouse harvests, including a lot of sample processing in the lab. I truly enjoyed the extensive time 'doing' research. It has been an incredibly productive and enjoyable summer combining skills with Erin. I'm excited by what the data will show in the coming months and to preparing our next application for funding! I'd like to publicly and formally thank Erin Sparks for hosting me at the University of Delaware this summer! I have enjoyed getting to know her team, learn about their work and solidify our collaborations and friendship! It has been truly amazing! Thank you!

Final day of ASPB Plant Biology, I'm too tired for other work pursuits, so what better way to finish the week than in a café blogging! The following covers my second week with Erin, ticking off an activity on my bucket list, and attending Plant Biology 2019! Delaware week 2!The second week in Delaware involved starting at the field by 7 am. Our current field experiment is combining our expertise and resources to look at strength/physiology tradeoffs and combines 3D imaging, resource uptake rates and mechanical properties of different soil-borne and aerial roots in maize. Since physiological processes change across the day we have tried to finish daily sampling before lunch (and before the temperatures soared into the mid 30s (degrees C)). The 3D imaging set up was put together over just a few days by the amazing Adam Stager who works with Erin! I'm so impressed with the talent and enthusiasm he oozes! It's no wonder every time I saw him he was surrounded by a cloud of undergrad groupies! I look forward to more impressive advances that he will no-doubt lead! The week ended extremely hot (high 30s) turning Erin's car into a very effective drying oven so the samples are all set to be ground, and weighed before we send them off for the next round of analysis! Redwoods - Check!The following week I had some recovery time and managed to tick off an activity on my bucket list: seeing redwoods in their amazing Californian cloud forests! This region is incredibly interesting for conifer diversity and if you want to know more I can highly recommend the In Defence of Plants podcast with Michael Kaufman. I did not make it as far north as the magic mile, but I still managed an impressive list of conifers, starting from a total lack of knowledge about northern hemisphere conifers (and with previous experience more around cycads and Araucaria species!) to a list of at least 17 species :) Plant Biology 20191400 plant scientists in one building! It's hard to describe! Chaos in a bubble?

The nice thing about this meeting is the ASPB community are very active on social media and on the Plantae platform. By day 2 a lot of people had written their twitter handle on their name tag and I'd met dozens of people I know, but have never met in person! In addition to running into cyber-friends, and some really interesting symposia, Plant Biology has loads of networking opportunities. 7 am speed networking breakfasts, group chats, open forums, careers advice and mentoring sessions as well as the usual posters and formal dinners. Bizarrely I repeatedly found myself in the 'mentor' seat for the first time at this meeting, having previously benefited as a mentee. I also had the great pleasure to hang out with the EEPP (Environmental and Ecological Plant Physiology) section of the ASPB. Wonderful people and I'm excited by the possibility of more ecophysiology talks at future Plant Biology meetings and future cross atlantic collaborations! Now, an early night I think, and then prep for next week's trip to Florida for the workshop: Linking Root Architecture to Function: Theory, methods and technology! The summer has begun and my travels along with it! Last week was the Society of Experimental Biology (SEB) conference in Seville, Spain and I'm now in Delaware, USA with Erin Sparks who I met on twitter, skype with monthly and until last Sunday had never met in person! To set the scene it's a sunny, humid 29 degrees Celsius outside, the tables are set for this afternoon's party. I have a bag of pretzel M&Ms (a new discovery!) open on the couch beside me, and the most adorable bull mastif called Izzy at my feet! SEB ConferenceConferences are a challenge for me for many reasons. For one I struggle with crowds and I'll go sit in a corner with my music playing in my headphones. But I also struggle with my own imposter syndrome. Some years this can be truly crippling but this year's SEB meeting was attended by some of the most amazing people. Along with catching up with friends and collaborators, I reconnected with Australian's I've not seen since I was a PhD student. There were also a lot of PEPG (Plant Environmental Physiology Group) members at the meeting and it was great to have an opportunity to discuss the details of next years Field Techniques Workshop in person. These different groups of positive and supportive people made this year a really positive experience. The great turnout of physiologists this year was down to the great selection of physiology sessions which also made it quite an intense week! The first day was filled with some really useful teaching sessions - I also presented my teaching using a mobile phone app. I learnt about some really useful tools including the Dejargoniser http://scienceandpublic.com/. This software was designed by Tzipora Rakedzon, a linguist working within the sciences to teach writing skills. the tool is free online and all you do is copy a section of text into the box click start and the highlighted text are words that would be considered jargon. It's a great tool to help with making writing accessible! The whole day was really useful and always a really nice group of people. The rest of the week was filled with really interesting plant physiology sessions with drought responses from the bottom up, then water use efficiency, and then in silico plants. Each of these talks were engaging and filled with excellent science! One experience casts a shadow on the plant science community and it's the behaviour of certain individuals. On the second evening I was out with a group of people for drinks. I wanted to ask someone (lets call them Bob) some questions about their talk. I went over to join the conversation. The other person was saying they work with people from my institution to which Bob aggressively told her the methods at Nottingham are crap and not reliable (and a bunch of other really nasty things about the people) and then said that he had the right tools that she should use. I was so shocked and disgusted by this behaviour that I walked away and talked to someone else, swearing never to work with this person (or their institution). I don't understand why some people can't just be good human beings. But the story gets worse... The next day I'm chatting with a colleague from a different institution and who should I see? Bob cosying up with one of the big names from Nottingham and looking at data on a laptop. It's one thing to not trust people from somewhere else, or to not be compatible personalities - I get that - but to publicly, aggressively insult those people one minute and brown-nose the next is utterly dishonourable. And I honestly struggle to understand people who do this or let this happen. When I'm setting up new collaborations it requires trust so I will never work (or share my data) with people who demonstrate a lack of integrity. The point of having collaborators is that I can't do what they do and so I need to know that the data they collect is reliable. Otherwise how can I be sure we wont be in a situation like this. Overall SEB was a really great week held in Seville - a beautiful city! I did manage a few hours in the centre one afternoon but I will definitely have to return! DelawareThe next leg of my summer travels brought me to Delaware to work with the amaizing Erin Sparks! Erin contacted me by twitter 2 years ago and we've been skyping regularly since, but when I stepped out of the airport in Philadelphia was the first time we had met in person! This first week has involved discussions, building our paper plan and preparing for a field harvest next week. Travel is also about learning other cultures. This week I've discovered pretzel M&Ms, the biggest bag of dried mango I've ever seen from Costco (as an Australian I get regular cravings for Mangoes that can almost be satisfied with dried mango), crab nachos and Corn Hole (a game that's really big over here). And then there's the language differences: cart/trolley, Koozie/stubby cooler, pruning shears/secateurs and granola/toasted muesli. Next week will be filled with science and data and icecream!

Stay tuned for the next edition of my travel blog. Just a quick blog to announce some more exciting news from AR_lab! This week has been the postgrad symposium and in line with our success last year Magda took home the coveted Agriculture and Environmental Science Poster 1st prize! Findi also gave her first talk and did a fantastic job! Although she didn't win an official prize, Findi has had the steepest learning curve and has improved the most of all my students. To me this means just as much as any official award!

So proud of my team! |

AuthorAmanda Rasmussen Archives

May 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed