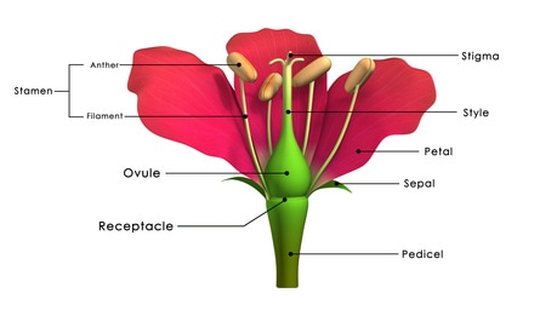

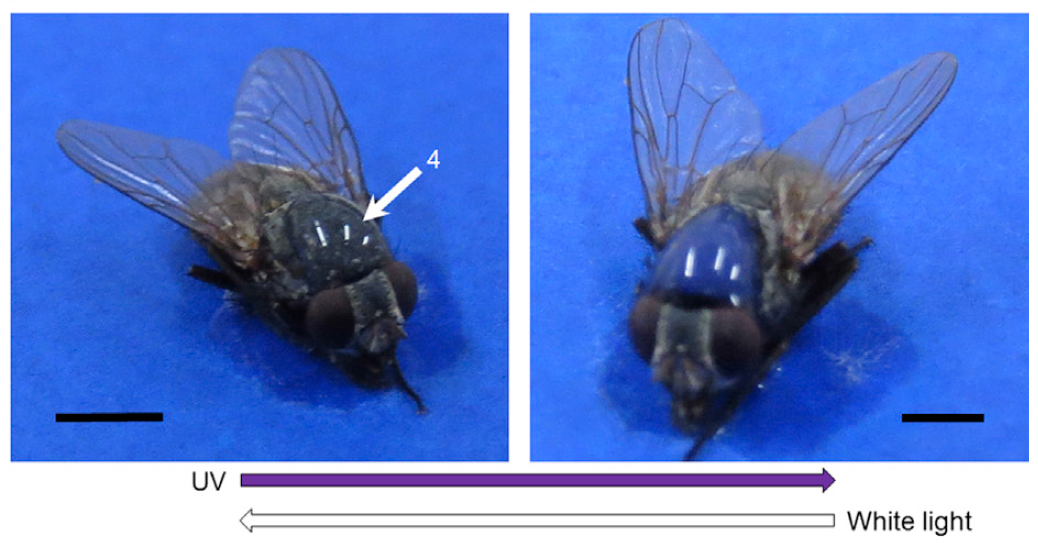

I love science fiction and I especially love Dr Who so when I find a chance to connect that love with my other love - plant science - I just have to blog about it! Last night's episode was filled with planty references but I can't go past the scene where a swarm of tiny robots are pollinating a wheat field (let's ignore the fact that wheat is wind pollinated for a minute) on a foreign planet. Fiction I here you say! Well… maybe not. To explore this out-of-this-world concept we first need to know what is pollination? According to my first year biology text book (Campbell, Reece and Mitchell) pollination is 'the placing of pollen onto the stigma of a carpel'. But what does that mean??? Let's use a picture to help. In plants, the male bits are the stamens with their anthers (which present the pollen), while the female bits are the carpels which include the stigma (sticky bit ready for pollen), the style (which the pollen tube grows down) and the ovary. Today's ramble is only about pollination but the rest of fertilisation (including pollen tube growth) is equally fascinating! (picture from: http://www.all-my-favourite-flower-names.com/parts-of-a-flower.html) Pollination can occur in many different ways including wind (as hay fever sufferers well know), animals and insects - bees being the most well-known and perhaps the most important economically. At this point, dear readers I highly recommend taking 7 minutes to watch this TED talk which has some nice pictures of pollination in action! Click Here Amazing right?! As many of you will be aware the bee populations have been declining due to a range of causes (some of which we still don't understand - and perhaps partly due to them returning to their home planet Melissa Majora as the Doctor told us in 2008!). At this point I want to say that our first priority should be to protect the bees (and all pollinators) but let's imagine for a moment we are travellers to a far away planet with no pollinators - could robots be the answer? Earlier this year a paper in Chem http://doi.org/10.1016/j.chempr.2017.01.008 made waves with their artificial pollinators. Many of you may have seen some of the headlines as you scrolled through Twitter but I wonder how many of you stopped and read the original article? I didn't - until today. So here is the roundup. The authors had a series of problems to overcome. The first was to find an adhesive that can pick up pollen efficiently but would also let go of the grains when in contact with the stigma (sticky female bit - see pic above), was non-toxic and water resistant. Their solution was an ionic liquid gel. The second problem was to determine if their gel was suitable for biological applications and non-toxic. They used a lab test on cells which were treated with the gel and found that small volumes had no significant effect on the number of living cells meaning that it was safe to use on biological systems. Ecologically, introducing little robots into the food chain could be a problem but the team could see their gel also being used for camouflage - reducing predation. Into their gel they mixed four different organic compounds which can change colour depending on the light and then painted flies and ants with the gel. As you can see (and I think this is as cool as the robotics part of this story) the gel changed colour with more UV light. The insects painted with the gel were able to move and interact within the flower, collecting pollen more effectively than non-painted insects. So they had a gel that worked on insects. The next challenge was to create a robotic insect. In insects the pollen gets transferred from the anther to hair on the insect's body. So the group coated different fibres with their gel and tested how well pollen would stick. The fibres came from everyday products like paint brushes and make-up brushes. They found the animal hair brushes (horse hair paint brushes) and nylon (from make-up brushes) worked well when coated with the gel but they found carbon fibres were unsuccessful because they were too big. They decided to stick with horse hair for future experiments because of biodegradability in the natural environment. The story is emerging: they have their sticky-gel, which is safe for use in the environment and now they have their fibres for mimicking pollinator hair - the only thing left is the flying machines! They used commercially available small UAVs (Unmanned aerial vehicle) which was just 42 mm long by 42 mm wide and 22 mm high. They stuck the gel-coated fibres on the back of the UAV with double sided tape (and checked that launch was unaffected by the fibres) and then used radiocontrols to fly the robotic bee to the Lilly flower, collect pollen and deposit it on the stigma - see the movie in the file below). They checked viability of pollination using microscopy and found successful pollen tube formation.

So although these UAVs may be slightly clumsy looking - they work. The next step is to make them smaller, fly more precisely and fly alone and then off-world robotic pollination might not be such a stretch of the imagination!

References: The article on robotic pollination can be found here: http://doi.org/10.1016/j.chempr.2017.01.008 and the colour-changing fly picture and the movie file come from this source. The textbook I used for pollination definition is: Campbell, Reece and Mitchell (1999) Biology (Fifth Edition) published by Benjamin/Cummings ISBN: 0-8053-6566-4. The TED talk on pollination comes from: https://www.ted.com/talks/louie_schwartzberg_the_hidden_beauty_of_pollination#t-437315 The flower picture came from this random website (it was the prettiest image!): http://www.all-my-favourite-flower-names.com/parts-of-a-flower.html

0 Comments

Link below isn't working: but this one is :)

http://www.nottingham.ac.uk/biosciences/events/holdenbotanylecture.aspx Come along on the 2nd May Feel free to get in touch if you have more questions. On the 2nd of May I'm honoured to be hosting Dr Sandra Knapp from the Natural History Museum (http://www.nhm.ac.uk/) for the Holden Botany Lecture.

The Holden Botany Lecture is a public seminar held once every two years and named after Prof. Henry Smith Holden who, in 1932, was our first Professor of Botany at the University of Nottingham. The first of these lectures was held in 1975 with the intention that the ‘lecture be given by a distinguished botanist, biologist, or an industrial or horticultural specialist, and would emphasise the importance of basic botanical and biological research work’. With this in mind Dr Sandra Knapp's impressive career working with the taxonomy of Solanum, Capsicum, and Lycianthes with the Natural History Museum clearly makes her a natural choice for this year’s seminar. The seminar is open to all so if you find yourself in the East Midlands do come along! More details for the event can be found at: www.nottingham.ac.uk/go/holdenbotanylecture or you can email me with any questions. See you on the 2nd May! |

AuthorAmanda Rasmussen Archives

May 2023

Categories |

||||||

RSS Feed

RSS Feed